Steve, November 2017 (1988)

I was very pleasantly surprised when Steve wrote to me. He is the father of the Giordano family interviewed in the 1968 Life-Magazine. They have become world famous in the village of Matala. He sent this wonderful story.

Giordanos in Matala, 1968; story written 1988

Life Magazine, in its July 19, 1968, issue told the story of Young American Nomads Abroad. Thousands of American youths were traveling the globe for a year or two, taking breathers from the stresses of home life, searching for life's meanings in other cultures and just plain taking advantage of the economic prosperity that made travel possible. They mingled with like-minded youth from other countries, largely British, South Africans, Germans, Australians, New Zealanders and Canadians.

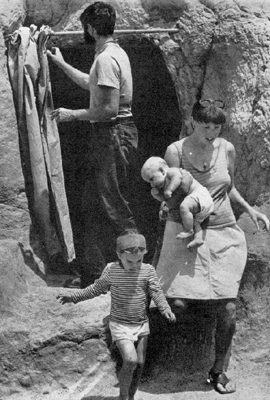

One group of nearly 100 lived in a community of caves on the southern coast of Crete, in the eastern Mediterranean Sea midway between mainland Greece and Egypt. Most were single, a few were married couples, and the Life reporter found one family of four (mine) whose second daughter had been born a few months before in Athens. We were staying in our van, parked in the courtyard of a Greek family in Matala, just across the beach from the wall of caves. The caves had been carved into the sandstone cliffs centuries before, and had been lived in sporadically since the Middle Ages.

Both communities liked us because our two young children made us somehow special. Other Greek families wanted us to move our van to their houses, and the tourists in the caves wanted us to live with them. Children have that familial effect on people. Maybe the tourists were reminded of siblings back home, or were simply tired of being around people their own age all the time.

If a child returns your interest, s/he verifies your worth. Teaching children something new is exciting and satisfying. Acting young with children is refreshing.

But traveling with children? Most people don't consider taking long family trips because the logistics look impossible. However, if travelers are open to the experience, long family trips can open new and fascinating parts of the world and its rich cultures.

For example: We stopped for a little picnic by the side of a country road on Crete. Under the shade of an olive tree, the blanket was laid out and food assembled. The four of us munched, chatted and drank as the children zoomed around between the blanket and wildflowers.

A Greek father and his son, who was about 12, and their donkey, appeared from nowhere. With huge smiles and an ebullient use of sign language, they made it known that these were beautiful children, that this trifle of food was inadequate for their health, and why eat in the fields like a poor shepherd when the hospitality of “me, Aristides and my family is so easily available?”

The boy and donkey were dispatched to their home, and Aristides hopped in our van to show the way. This casual encounter in the countryside resulted in our tourist family and our gracious host becoming celebrities in the small town. It involved tours of several homes, with food in each and every one, topped off by a wedding celebration in the plaza with dancing till 2 a.m.

Tourists with children make quite a different impression than tourists without them. It's human nature to feel a little suspicion toward strangers, but children somehow disarm that suspicion. It's not hard for a sensitive tourist to establish relations in a host country, but the presence of children makes it automatic.

Curiosity about the children bubbles forth into questions, comments and, frequently, invitations. The tourists are OK; their presence in a foreign land is presumed legitimate. It's almost as if the children are ambassadors between the contrasting cultures and languages,

Children are quicker to smile than adults and,by definition, they’re cute. Attention focuses on them as maternal and paternal feelings erupt into invitations for dinners, lodgings and often parties and festivals. Children bring good luck, and making them happy makes the host happy.

THE TRIP

In the mid-1960s, when career planning didn't hold the urgency that it does today, taking a year or so to travel was an "early-in-a-lifetime" thing to do. Individuals and couples could plan, save money for a few years and take the Grand Tour, much in the tradition of the British "going out to India" in the days of the Empire.

We figured $7,000 might last a year. We figured that after deducting $2,400 for round-trip trans-Atlantic boat tickets, expenses couldn't be more than $12 per day for a family of four.

Were we crazy or what? Most friends and relatives thought so. Travel with children was viewed as impossible, much less desirable. Adding the impending birth to the mix was considered reckless.

We realized that the only hope of success for a yearlong trip with children was for the family to have its own camper. Besides the obvious advantage of spending less money for accommodations, meals could be prepared at will, and more supplies could be carried, like diapers, clothes and food. The baggage eventually included a tricycle, rocking chair, dolls, and boxes of souvenirs and toys

The biggest advantage of traveling "turtle-back" turned out to be the ease of arriving at destinations. There was no unpacking and repacking, no suitcases to lug and, our room-with-kitchen was always just what we wanted, parked in a campground with a choice view.

Buying a used French bread-delivery van, with tall roof, was the first major destination expense: $400. Found objects, such as baskets, boards and crates, filled out the interior. The essential tool was a Swiss army knife complete with saw.

THE BIRTH

An important decision concerned the imminent birth of Sarah. It was “scheduled” to happen December 23, but who knew for sure? Even if her mom was an obstetrical nurse, birthing on the road or in a campground would be too risky and no fun. The road from Paris to Athens, via the unpaved mountains of southern Yugoslavia, caused lots of bouncing worries.

The plan was to arrive in Athens in early December and rent an apartment through the winter months. Contacts at the U.S. Air Force base there (Air Force wives have babies, don't they?) referred us to a good Greek doctor specializing in obstetrics.

The hospital delivery went as scheduled with no hitches or glitches. Mom and the baby prospered during the following three months in Athens. Parks, a zoo and downtown were within walking distance of the $65/month apartment.

THE TRIP CONTINUES

Adding a baby-sleeping basket just under the roof of the "camper" kept the rolling nursery organized and tidy. Adding baby Sarah to the family passport at the U.S. Embassy kept border crossings organized and tidy.

The second three months of her life were spent on southern Crete, camped in the dirt plaza of Matala, adjacent to a house of widows and children who were happy for the visit. Father did the cooking and mom the cleaning. Diapers dry quickly on Mediterranean islands, especially when left on fallen Roman columns that had lain in place for 2,000 years.

It was thus a trip of perspective for the parents. After a few months on Crete, we traveled to places that, 20 years later, have become t-shirt destinations. As for the children, they seemed to prosper and grow as well as they might have at home. Doctors and medicines were occasionally required, but they were available everywhere, as were playmates for the children

Greeks insisted the name Giordano was Greek, and Italians insisted it was Italian. It was both. My parents and sister joined the trip for a few weeks. The breadth and depth of family was thus reinforced as we all met dozens of relatives in Sicily and Milan for the first time.

The trip that took a year and a day was far more enriching for the parents as a direct result of including the children. Did the children prosper as well? Did their year of life in Mediterranean cultures leave any lasting impressions?

SARAH

"My friends don't really talk much about where they were born, but it comes up in conversation," says Sarah Giordano, age 21. She was born in Athens in 1967, during her family's one-year travels through southern Europe. She is currently majoring in Psychology at Western Washington University in Bellingham, WA.

"Most people think its neat that I was born in Greece. Some seem to be a little embarrassed to admit that they were born in Bellingham."

Since her grand tour of southern Europe ended when she was only nine months old, Sarah has no retrievable memories of it. But the wealth of photographs taken by her mother on the trip, plus all the family talk over the years, has given Sarah strong feelings about Greece that border on sense memory.

"Mom has so many pictures of the trip, pictures of people that look just like the people in movies I see in my culture class in school. For example, one movie showed a mother pinning a bead on a child - to ward off the evil eye, I thought, 'I've got one of those.'"

The evil eye should never even look askance at Sarah during her lifetime if the efforts of Greeks during her early months bear any fruit at all. Hundreds of people went through the motions of spitting on her as an infant. It wasn't really spitting; more like blowing a tobacco flake of the lips. The purpose was to show that, just in case the evil eye was watching all the fawning attention, this was not a baby worthy of the evil eye's attentions.

Films on television that show scenes of Greece tug at Sarah's feelings of attachment. She's aware that some of her distant ancestors lived in Greece 500 years ago.

Does she want to go back someday? "Sure. I feel a special warmth toward Greece. I'd really like to go back and learn more about it.

"I was talking to a friend who was born in Germany. He really wants to go back to learn about it, but I only want to go to Greece."

When Sarah was about four months old, she was left napping in her bread basket/bed in the van while her parents and sister explored a deep natural cave just off a country road on Crete. Within 20 minutes an alarming presence appeared at the mouth of the cave, but it turned out to be just a curious man wondering who owned the van. He asked for a ride to town and hopped into the van just as Sarah was waking up, peeking over the top of her sleeping basket.

Such a roar of surprised happy laughter has never been heard; it was as though he had found the treasure of the Sierra Madre. He chortled all the way to town and told the story of his discovery to anyone who stopped by our taverna table in the town plaza. Ouzo, olives and cheese refreshed our palates for over an hour.

Sarah's middle name is Melina, which is Greek for honey. She was named after Melina Mercouri, the Greek movie star and singer who so epitomizes the Greek spirit and became their Minister of Culture.

"I just went through this last night with the guy born in Germany," she said. "It's embarrassing, because most people have never heard the name Melina, but he thought it was beautiful. Then I told him that it meant honey, and that was OK. Then I told him who it was after."

She may not be aware consciously of the early influences in her life, but for some reason, Sarah's favorite courses in college are about cultures different from her own.

LORI

Lori Giordano, age 24, spent the third year of her life overseas traveling with her parents and younger sister, who was born on the trip. Lori has a BA in Finance, Marketing and Decision Sciences from Western Washington University, in Bellingham, WA.

"Just the other day I saw a show about analyzing people by analyzing their first memories," said Lori recently. "It was interesting, because I remember. The first memory I have was of going to the hospital, because Mom was having Sarah. I remember going there in the car."

World traveling isn't much of a topic of conversation among her friends. Most people who have traveled weren't nearly so young, so their memories and the things they learned are really quite different from Lori's. Her actual times spent going from one place to another aren't remembered, nor are many of the people she met.

But those distant places, environments, now mean a lot to her. "I have flashbacks every once in a while. I can remember snails, and the caves," she said, recalling the three months spent in Matala, the coastal town on southern Crete that was home to a large cave community of world travelers. Snails were a delicacy to the Greeks. During World War II, snails were survival food. "I remember salt in dried puddles on the rocks," she added.

Does she feel cheated by being so young on the trip - too young to benefit from it? "I don't think so since I can remember some things.

"When I was in classes that taught about other parts of the world, I could think back and just know that we're not the center of the world or universe, but that's what some people think who haven't traveled."

At age 15, before starting high school, Lori spent three weeks visiting relatives in Italy with her father, stepmother, sister, aunt and grandparents. "I remember everything about that trip," she said. She enjoyed the time in Sicily the most. "It was so much more peaceful, I didn't even want to come home."

The pace and breadth of life in rural Sicily seemed idyllic - a shepherd's wife would be the life for her. One day, everyone in the family who could fit in the rental van drove several miles out of town to the shepherd's flock and hut for a day in the countryside. We all helped make cheese and yogurt in a giant cauldron and had the sort of day one remembers forever.

The shepherd's wife, who was nearly 40, had never spent such a day before. It took the tourist relatives from America and their rented van to take her where she'd never been. Her husband and sons spent most of their lives in the fields and mountains, but she had never been out of the village. Learning that, Lori realized that the peasant life might be OK for men, but it would be no life for a woman.

Home from the vacation, she knew home was where she'd rather be. "Wherever you are, you see things differently," she reflected.

...

Steve Giordano